MEDIEVAL HISTORY

Let's Understand What Does "Kashmir" Mean

According to folk etymology, the name “Kashmir” means “desiccated land” (from the Sanskrit: ka = water and shimīra = desiccate). In the Rajatarangini, a history of Kashmir written by Kalhana in the mid of 12th century, it is stated that the valley of Kashmir was formerly a lake. According to ancient Hindu text, the lake was drained by the great rishi or sage, Kashyapa (Photograph towards left), son of Marichi (son of Brahma, the creator of the universe) by cutting the gap in the hills at Baramulla (Varaha-mula).

Amazingly, a bird’s eye view, courtesy Google Earth. The geography of Kashmir valley matches perfectly with the ancient Hindu text. Clearly the valley, with river Jhelum as its principal drainage seems a vast lake of sea proportions. It drains out even today through a gorge near Baramulla, the Varahmula of ancient times.

When Kashmir had been drained, Rishi Kashyapa asked Brahmins to settle there. The name of Kashyapa is by history and tradition connected with the draining of the lake and the chief town or collection of dwellings in the valley was called Kashyapa-pura, which has been identified with Kaspapyros of Hecataeus (apud Stephanus of Byzantium) and Kaspatyros of Herodotus.

Historical Accounts by Kalhana's Rajatarangini

Kalhana’s Rajatarangini (River of Kings), all the 8000 Sanskrit verses of which were completed by 1150 CE, chronicles the history of Kashmir’s dynasties from earlier times to the 12th century. It relies upon traditional sources like Nilmata Purana, inscriptions, coins, monuments and Kalhana’s personal observations borne out of political experiences of his family. Towards the end of the work mythical explanations give way to rational and critical analyses of dramatic events between 11th and 12th centuries for which Kalhana is often credited as “India’s first historian”.

During the reign of Muslim kings in Kashmir, three supplements to Rajatarangini were written by Jonaraja (1411–1463 CE), Srivara, and Prajyabhatta and Suka, which end with Akbar’s conquest of Kashmir in 1586 CE. The text was translated into Persian by Muslim scholars such as Nizam Uddin, Farishta and Abul Fazl. Baharistan-i-Shahi and Haidar Mailk’s Tarikh-i-Kashmir (completed in 1621 CE) are the most important texts on the history of Kashmir during the Sultanate period. Both the texts were written in Persian and used Rajatarangini and Persian histories as their sources

Early History - Hinduism and Buddhism

During the later Vedic period, as kingdoms of the Vedic tribes expanded, the Uttara–Kurus settled in Kashmir. In 326 BCE, Porus asked Abisares, the king of Kashmir to aid him against Alexander the Great in the Battle of Hydaspes. After Porus lost the battle, Abhisares submitted to Alexander by sending him treasure and elephants. During the reign of Ashoka (304–232 BCE), Kashmir became a part of the Maurya Empire and Buddhism was introduced in Kashmir. During this period, many stupas, some shrines dedicated to Shiva and the city of Srinagari (Srinagar) were built. Kanishka (127–151 CE), an emperor of the Kushan dynasty, conquered Kashmir and established the new city of Kanishkapur. Buddhist tradition holds that Kanishka held the Fourth Buddhist council in Kashmir, in which celebrated scholars such as Ashvagosha, Nagarjuna and Vasumitra took part. By the fourth century, Kashmir became a seat of learning for both Buddhism and Hinduism.

Kashmiri Buddhist missionaries helped spread Buddhism to Tibet and China and from the fifth century CE, pilgrims from these countries started visiting Kashmir. Kumārajīva (343–413 CE) was among the renowned Kashmiri scholars who traveled to China. He influenced the Chinese emperor Yao Xing and spearheaded translation of many Sanskrit works into Chinese at the Chang’an monastery.

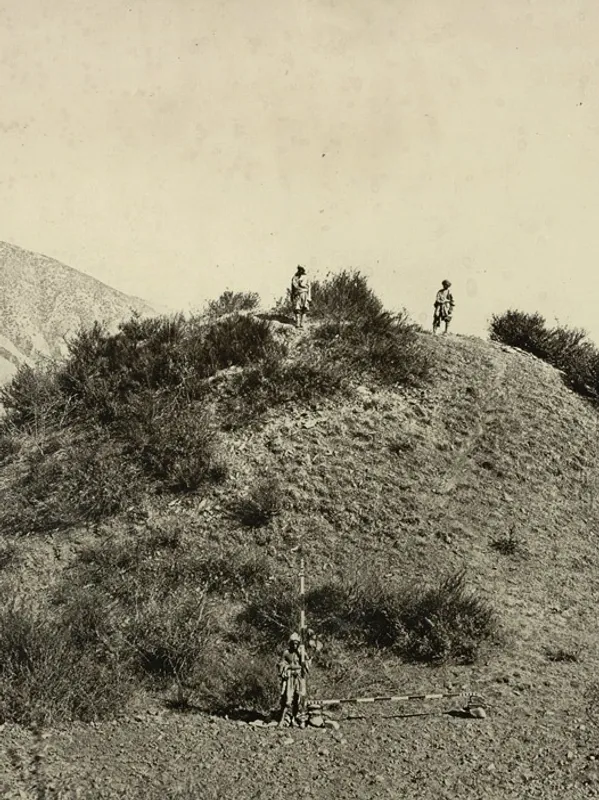

The photograph towards left gives a general view of the unexcavated Buddhist stupa near Baramulla, with two figures standing on the summit, and another at the base with measuring scales, was taken by John Burke in 1868. The stupa, which was later excavated, dates to 500 CE.

Shaivism and Hindu Dynasties (7th - 14th Century)

A succession of Hindu dynasties ruled over the region from the 7th-14th centuries. After the seventh century, significant developments took place in Kashmiri Hinduism. In the centuries that followed, Kashmir produced many poets, philosophers, and artists who contributed to Sanskrit literature and Hindu religion. Among notable scholars of this period was Vasugupta (875–925 CE) who wrote the Shiva Sutras which laid the foundation for a monistic Shaiva system called Kashmir Shaivism. Dualistic interpretation of Shaiva scripture was defeated by Abhinavagupta (975–1025 CE) who wrote many philosophical works on Kashmir Shaivism. Kashmir Shaivism was adopted by the common masses of Kashmir and strongly influenced Shaivism in Southern India.

In the eighth century, the Karkota Empire established themselves as rulers of Kashmir. Kashmir grew as an imperial power under the Karkotas. Chandrapida of this dynasty was recognised by an imperial order of the Chinese emperor as the king of Kashmir. His successor Lalitaditya Muktapida lead a successful military campaign against the Tibetans. He then defeated Yashovarman of Kanyakubja and subsequently conquered eastern kingdoms of Magadha, Kamarupa, Gauda, and Kalinga. Lalitaditya extended his influence of Malwa and Gujarat and defeated Arabs at Sindh. After his demise, Kashmir’s influence over other kingdoms declined and the dynasty ended in 855–856 CE.

The Utpala dynasty founded by Avantivarman followed the Karkotas. His successor Shankaravarman (885–902 CE) led a successful military campaign against Gurjaras in Punjab. Political instability in the 10th century made the royal body guards (Tantrins) very powerful in Kashmir. Under the Tantrins, civil administration collapsed and chaos reigned in Kashmir till they were defeated by Chakravarman. Queen Didda, who descended from the Hindu Shahis of Udabhandapura on her mother’s side, took over as the ruler in second half of the 10th century.

After her death in 1003 CE, the throne passed to the Lohara dynasty. Suhadeva was the last king of the Lohara dynasty. His wife, Queen Kota Rani ruled until 1339. She is often credited for the construction of a canal, named “Kutte Kol” after her, diverting the waters of the Jhelum to prevent frequent flooding in Srinagar. During the 11th century, Mahmud of Ghazni made two attempts to conquer Kashmir. However, both his campaigns failed because he could not take by siege the fortress at Lohkot.

The photograph towards right showcases the Martand Sun Temple Central shrine, dedicated to the deity Surya.

The temple complex was built by the third ruler of the Karkota dynasty, Lalitaditya Muktapida, in the 8th century CE. It is one of the largest temple complex on the Indian Subcontinent.

Muslim Rulers (14th - 19th Century) Prelude and Kashmir Sultanate (1346–1580s)

Rise of feudal lords (Damaras) and other domestic political reasons during rule of the Lohara dynasty (1003–1320 CE) paved the way for foreign invasions of Kashmir. Rinchana was a Tibetan Buddhist refugee in Kashmir, who had established himself as the ruler after Zulju. Rinchana’s conversion to Islam is a subject of Kashmiri folklore. He was persuaded to accept Islam by his minister Shah Mir, probably for political reasons. Islam had penetrated into countries outside Kashmir and in absence of the support from Hindus, who were in a majority, Rinchana needed the support of the Kashmiri Muslims. Shah Mir’s coup on Rinchana’s successor secured Muslim rule and the rule of his dynasty in Kashmir.

In the 14th century, Islam gradually became the dominant religion in Kashmir. With the fall of Kashmir, a premier center of Sanskrit literary creativity, Sanskrit literature there disappeared. Islamic preacher Sheikh Nooruddin Noorani, who is traditionally revered by Hindus as Nund Rishi, combined elements of Kashmir Shaivism with Sufi mysticism in his discourses.

Sultan Sikandar (1389–1413 CE) on the directions of the Sufi “saint”, Mir Mohammad Hamadani, committed innumerable atrocities against non-Muslims in his reign. Large numbers of Hindus were converted (forced conversions), many fled or were killed for refusing to convert to Islam. Sikandar earned the sobriquet of but-shikan or idol-breaker, due to his actions related to the desecration and destruction of numerous temples, chaityas, viharas, shrines, hermitages and other holy places of the Hindus and the Buddhists.

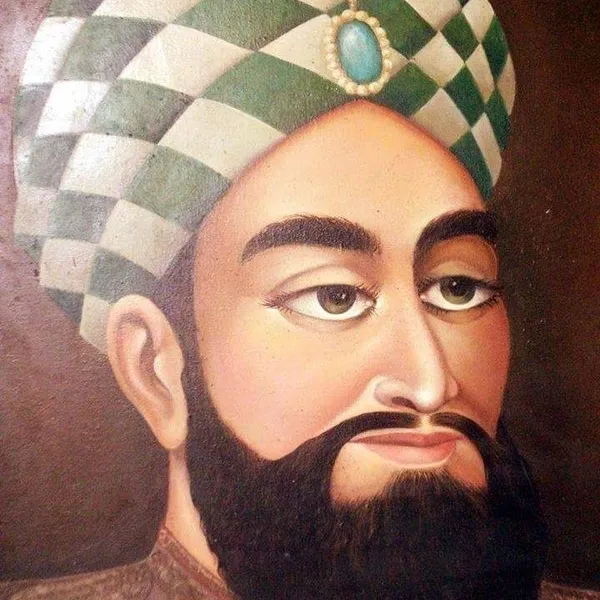

Sultan Zain-ul-Abidin (Photograph towards Right, 1420–1470 CE) invited artists and craftsmen from Central Asia and Persia to train local artists in Kashmir. Under his rule the arts of wood carving, papier-mâché, shawl and carpet weaving prospered. For a brief period in the 1470s, states of Jammu, Poonch and Rajauri which paid tributes to Kashmir revolted against the Sultan Hajji Khan.

However, they were subjugated by his son Hasan Khan who took over as ruler in 1472. By the mid 16th century, Hindu influence in the courts and role of the Hindu priests had declined as Muslim missionaries immigrated into Kashmir from Central Asia & Persia and Persian replaced Sanskrit as the official language. Around the same period, the nobility of Chaks had become powerful enough to unseat the Shah Mir dynasty.

Mughal general Mirza Muhammad Haidar Dughlat, a member of ruling family in Kashgar, invaded Kashmir in 1540 CE on behalf of emperor Humayun. Persecution of Shias, Shafi’is and Sufis and instigation by Suri kings led to a revolt which overthrew Dughlat’s rule in Kashmir.